Download and print as a PDF (483kB pdf)

On this page

- What is this information about?

- Why have I been given this information?

- What is an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)?

- What important things do I need to know about having an IPC put in?

- How is the tube put into my chest?

- How long do I stay in hospital?

- How does the drain stay in place?

- Who will drain the fluid from my tube once it is in place?

- How soon can I drain the fluid and how often do I need to do this?

- What are the risks of having an IPC?

- Are there any risks from having an IPC in for a long time?

- What happens after I have the IPC put in?

- Who can I contact if I need further information or help?

What is this information about?

This information is about having an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC) put in. It explains:

- what an IPC is

- how having an IPC can help if you need to have fluid drained from your chest often

- what will happen when the IPC is put in

- what to do after you have had the IPC put in

Why have I been given this information?

You have been given this information because you have had fluid drained from your chest. We need to manage this fluid and inserting an IPC will make this easier. You may already have a diagnosis which explains why the fluid is building up.

We will also discuss different ways of managing this fluid with you.

What is an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC)?

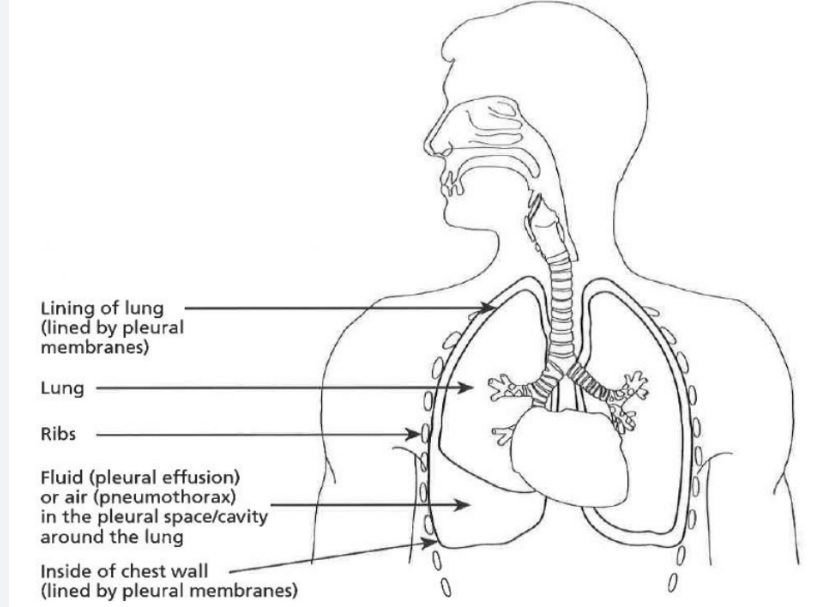

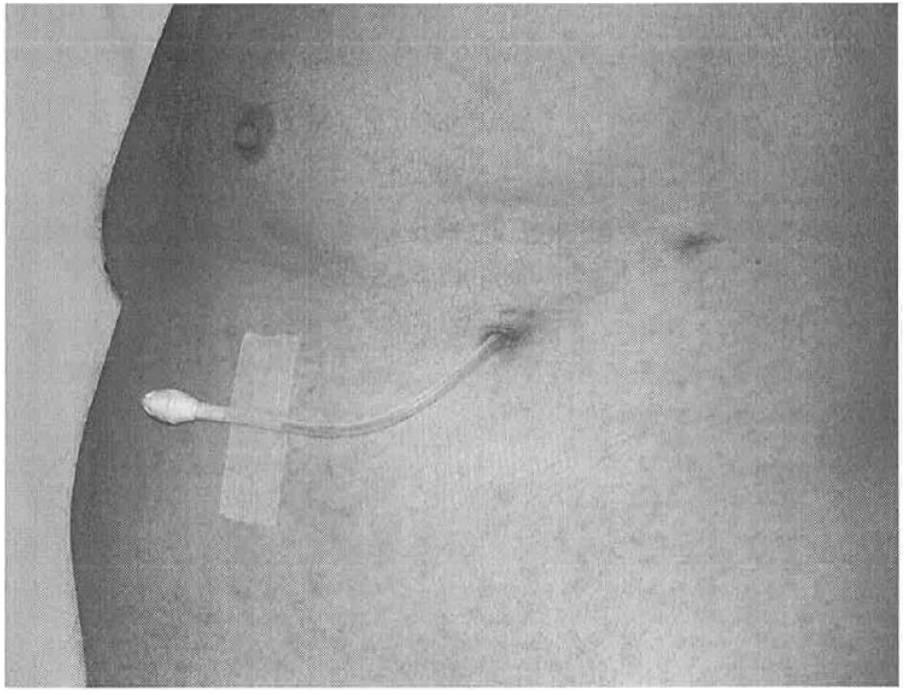

An IPC is used to drain pleural fluid from around your lungs. It is a soft, flexible, tube thinner than a pencil. It stays inside your chest. The end of the tube passes out through your skin. There is a valve on the outer end of the tube to prevent fluid leaking out.

When you have an IPC, pleural fluid can be drained from your lungs painlessly whenever this needs to be done. You will not need to have uncomfortable injections and chest tubes.

There is an area called the pleural space in your chest. This made up of two thin membranes (strong, thin layers); one lines your lung, and the other is lining your chest wall.

Between these layers there is usually a very small space which contains a small amount of fluid. This can build up for a variety of reasons and may make you feel breathless.

Draining away the fluid using needles and syringes helps relieve the breathlessness. After a while, the fluid will often re-collect making you breathless again. Drainage can be done like this several times, but it can be uncomfortable and means many trips to hospital.

The IPC allows fluid to be repeatedly drained without you having to come to the hospital.

What important things do I need to know about having an IPC put in?

- Tell your doctor about all the medication you take and any medical conditions you have.

- Tell us if you are on any blood thinning medications. These are normally stopped before the IPC is put in. Do keep on taking any other medications (including those for high blood pressure).

- If you are given sedation (medicine to make you relaxed and sleepy) when you have the IPC put in, for the next 24 hours do not drive; return to work; operate machinery; drink alcohol; sign legal documents or be responsible for small children.

- You do not need to be nil by mouth (not have anything to eat or drink) before the IPC is put in. Do have a light breakfast.

- We will contact you to arrange a time for you to have your IPC put in.

- You will have the IPC put in at the pleural clinic.

How is the tube put into my chest?

- You will be asked to either sit or lie in a comfortable position by the doctor.

- An ultrasound scan of your chest will be done to find the best position for the drain. This is painless.

- After you are settled, your skin will be cleaned with cold alcohol wipes. Then, a local anaesthetic will be injected. This might cause mild discomfort, which will pass quickly.

- Your doctor will then make two small cuts in the numb area of your skin and create a path for the IPC. This should not be painful although you may feel some pressure or tugging.

- The IPC is then gently positioned into your chest, and a sterile dressing will be put on.

How long do I stay in hospital?

If there have been no problems, you will be able to go home on the same day as the IPC is put in.

Do arrange to get someone to drive you home.

How does the drain stay in place?

IPCs are a long-term solution for fluid issues. To hold the tube securely in place a soft band is applied under the skin. The skin heals around the band keeping it securely in place and stopping it from coming out.

Two stitches will be put in when your tube is put in. The doctor will say how soon these should be removed. This is usually after 7 to 14 days.

IPCs can be taken out if they are not needed anymore.

Who will drain the fluid from my tube once it is in place?

Draining the fluid is an easy procedure.

To start with, a district nurse will come to your home to do the drainage.

If you prefer you or someone you know can take over. However, in special cases, a respiratory nurse may do it in hospital.

We will make these arrangements so you will not need to organise any of this for yourself.

How soon can I drain the fluid and how often do I need to do this?

When the doctors insert the IPC, most of the fluid in your chest will be removed at the same time. How often drainage is needed is different from person to person. It might be daily, weekly, or even less often.

The gap between the times you have drainage can be longer or shorter depending how soon fluid builds up for you.

We will talk with you and the District Nurses about your drainage plan.

What are the risks of having an IPC?

For most people, having an IPC put in is safe, but a few IPC insertions can cause problems. All of these can be treated by the doctors and nurses.

Most people get some discomfort from their IPC in the first week. You can take painkillers such as paracetamol to control this.

Sometimes IPCs can become infected and the infection needs treatment. This is rare and happens to about 1 in 50 people. The doctor will clean the area around the IPC before it is put in to try to prevent this. You will also be shown how to keep it clean yourself.

Do tell your GP or District Nurse if you have anything such as fever, increasing pain, or redness after your IPC is put in. Or contact the respiratory nurses on the number below.

When an IPC is put in it may damage a blood vessel causing serious bleeding. Every effort will be made to stop this from happening and so it is rare (less than 1 in 500 cases).

If it does happen, it is a serious issue and an operation to stop the bleeding may be needed.

Are there any risks from having an IPC in for a long time?

It usually is safe for IPCs to be left in place for as long as they are needed.

The main risk is of a chest infection caused by germs getting into the chest through the IPC. You can reduce the risk of this by following the instructions you have been given for caring for your IPC and for keeping things clean and disinfected (having good hygiene).

Do let the doctors know if you develop a lump or any pain around your IPC after it is put in. They will advise you on the right treatment.

What happens after I have the IPC put in?

It takes around 30 to 60 minutes to put in the IPC. We will give you an x-ray to make sure the drain is in the right place and then drain your chest.

Whether or not you had medication to make you relaxed and sleepy while your IPC was put in do make sure you have someone:

- to drive you home or to be with you if you take a taxi home

- to stay with you overnight in case you feel unwell

Do not use public transport to get home after you have had your IPC put in.

Who can I contact if I need further information or help?

Respiratory Nurse Specialists

St Richard’s Hospital, Chichester

01243 831 597

Chichester

[email protected]

Worthing Hospital

01903 205111

Ext. 85858

Worthing

[email protected]

Please call Monday to Friday 8.30am to 5.00pm. If your call is not answered, please leave a message and a Respiratory nurse will return your call.

This information is intended for patients receiving care in Chichester St.Richard’s hospital and Worthing hospital.

The information here is for guidance purposes only and is in no way intended to replace professional clinical advice by a qualified practitioner.